China’s Twitter-like Weibo nearly boiled last week, as Taiwanese pop star Jay Chou, whose last album was released in 2012, defeat Cai Xukun, the current most popular celebrity in China, in a battle of the “Super Hashtag” on that social network.

It is a battle of popularity, in which young idols compete for higher rank and longer time on the trending page, most of the time without themselves even doing anything. That’s because the fans are so dedicated that they do costly things to send their idols the top, such as pressing likes and donating money to Weibo on their idols’ behalf, voluntarily.

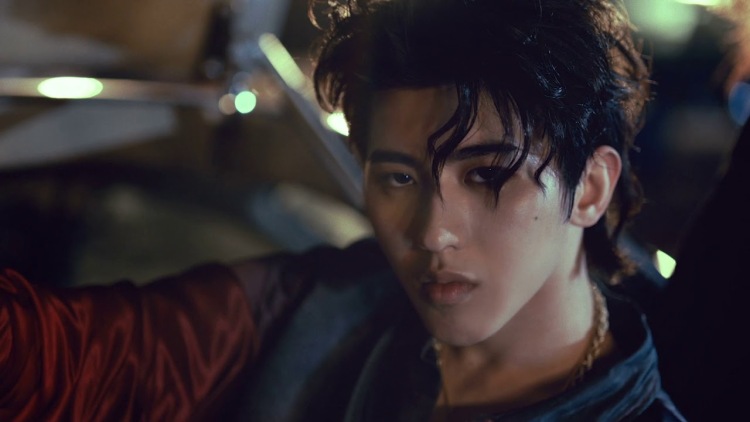

The throne of the Super Hashtag had long been taken by Cai Xukun, a Chinese pop star and the winner of reality show Idol Producer, in which young males show off their talents and charisma to attract viewer votes. He remained on the throne because his fans were much larger in number and more cultish compared to fans of other celebrities.

But these fans never anticipated that their idol could be dethroned by a nobody to them.

A few weeks back, in a question posted on Douban, another Chinese social network, one user questioned why tickets for Jay Chou’s concert is so difficult to buy, given the fact that Chou’s ranking on the Super Hashtag is so low.

That question triggered the silent majority.

Chou was indeed a nobody on the Super Hashtag. In fact, he is not even on Weibo. But in the good days of the millennials’ all-time favorite singer-songwriter, he was massively popular, if not more popular than today’s Cai. The award-winning 40-year-old had sold more than 30 million albums during his prime time, and is widely accepted throughout Asia.

Chou’s fans, many of whom are a few years younger than their idol, were not familiar with the rules of the Super Hashtag at first. They did not quite understand the mentality of Cai’s fans, specifically why were they so obsessed with their idol’s rank on the Super Hashtag, that they pull money out of their own pockets to boost it.

But Chou’s fans were more angry than confused when they saw that Douban post. They devised the biggest popularity heist in the history of Chinese fandom.

They studied the rules, very quickly. They did the same things as their counterparts would do. They pull money out of their own pockets.

When it wasn’t enough, they formed alliances with fan groups of other pop stars in the same age range, such as the rock band Mayday, and the Malaysian singer Stephanie Sun.

Finally, they pulled it off. After 16 hours, Chou dethroned Cai on the Super Hashtag ranking. During the period, more than 5 million virtual items were bought on the Weibo platform to boost both singers’ rankings, resulting in an estimated 10 million RMB revenue surge for the social media company.

An Ironic Poke at the Fan Economy

“Who said Jay does not have internet traffic? It’s because we don’t do it!” said one of Chou’s fans in her victory remarks, “Those who have strong talents do not need traffic to prove themselves.”

Even China’s state-owned television network CCTV posted on its Weibo account that “perhaps Jay era will be gone, but it will not be weeded out by traffic. Talents make a man go further.”

Chou’s landslide win was also an indication of shifting public opinion towards Gen Z idols. Poll data of Chou’s supporters in the battle showed that only 51.75 were dedicated fans. 27% were those who had a generally positive impression on him but did not identify as a fan. Here comes the interesting part: 21% were not a fan of Chou nor Cai, but chose to support the former.

Meanwhile, what Cai’s side did during the battle was a textbook exhibition of the ironic modern-day fan economy in China. Cai’s agency encouraged fans to resort to click farming. Many of his fans also had to register several accounts and some even purchased bot accounts to bypass the daily vote limit, a justifiable mean they were already familiar with.

Ultimately, both sides did the same thing, wielding the power of the masses to cheat platform that was in some way designed to be cheated. However, on Chou’s side, participants largely remain convinced that they are doing the long overdue justice to the fan economy and the social media in general that was previously fueled by unhealthy vanity, treating the fraudulent system in its own way.

“I think many people were just simply sick of Cai always at the top and his cultish fans, so they chose to support Chou”, a popular Weibo post said.

But Wait… What is China’s Fan Economy?

“No Fan, no market” is an increasing prevalence in China’s entertainment industry. Fans, once merely mental supporters for their idols and the passive recipient of TV advertising and marketing campaigns, are showing a stronger than ever presence.

Like in many other countries where entertainment industries prosper, the popularity of an idol in China was once largely based on how good their music albums or tv shows perform, how many awards they receive, etc. Nowadays, it is defined by how many fans an idol has, and how dedicated they are to devote time and money to generate extra internet traffic for their idol.

They could do that by registering multiple accounts on social media websites and feverishly reposting posts created by their idols or other prominent fans, so that relevant hashtags can stay longer on trendings.

A Weibo promoting British soccer team Manchester United, sent by Lu Han, a Chinese singer-dancer and ex-Kpop boy band member in 2012, was reposted by his fans for 42 million times in 2016 for no apparent reason other than breaking the record of 38 million times, which was previously held by Karry Wang Junkai, another young Chinese boy band member who achieved that when he was only 15.

Those numbers took fans years to maintain, and to illustrate how much crazier Cai’s fans were: he got more than 14 million likes and 10 million reposts almost instantly after posting a music video celebrating his 20th birthday.

While that the performance of these idols’ work still matters, it’s just not that crucial anymore, considering the fact that another way fans could help their idol is to rush to iTunes/Spotify and purchase or stream their idol’s songs, on heavy rotation. And before you ask, yes. They’d take the risk and venture beyond the Great Firewall to do one for the team.

One example was Kris Wu, a Canadian-Chinese singer and ex-teammate of Luhan, is very popular in China but a lesser known in the west. He, or more specifically his fans, were accused of using bots to boost the sales of his new album Antares—knocking American pop stars including Grande and Lady Gaga off top spots on the charts in 2018, which lead to fiery discussions on Twitter. Users in Europe and the United States have been asking the question: “Kris Wu, Kris Who? ”

These examples, are in essence, what China’s fan economy is about. But one may still wonder: how did these fans achieve that? Well it turns out that the way fans boost idol’s popularity is more of an organized crime than simple crowd work.

Fans join multiple larger fan clubs, which have corporate-like structures that consist of key departments such as internal and external communication, art design, copywriting, data gathering, and marketing. These clubs are often managed through instant messaging apps such as Tencent’s QQ or WeChat. For some of the most popular Chinese celebrity like Cai, some of their most prominent fans (they are called ‘fan heads’) who exhibit organizing skills through managing clubs are often paid and some even hired by the agencies.

In their corresponding clubs, these leaders conduct online meetings and issue orders to individual fans or department heads, whose role is to follow, comment and forward a celebrity’s posts, and initiate discussions and market campaign for the most-heated topic.

And that led to another problem in the social media era.

Fake Data

It is no secret and that with the way the fan economy works, the celebrities engaged in the above mentioned activities are faking their online popularity by hiring fans and using bots. And when they are faking it for long enough, they would have made it.

Spending money to improve social media rankings has become the norm in China’s entertainment industry. In response to the growing demand, even a professional industrial chain was born. A fan of a Chinese idol whose name the fan did not wish to expose bluntly said that she and her like-minded folks can easily purchase a huge number of third-party services to enhance their idol's ranking on Weibo.

According to data compiled by iResearch, only 30% of the engagement on celebrity Weibo accounts is organic and comes from real people, and the rest is generated by bots or fans hired or ordered to participate in fraudulent activities.

In recent years, more and more movies and tv shows were tempted to cast these online celebrities, so that they can tap into their massive fan base and boost ratings, viewership and box office proceeds, even if the idols are not known for their talents in acting. As long as there’s popularity, there’s public attention and profitability.

Besides, inside the fanatic fans group, a special fund-raising channel exists. When critical moments arrive, groups will raise funds from the entire fan community—the money will be used to maintain the star’s popularity, increase album sales, etc.

Some of the prominent fan heads even provided step-by-step instructions for other followers to fake the idols’ album sales on iTunes, such as how to set up US Apple IDs, purchase and redeem gift cards, as well as ways to boost sales/streaming hours without triggering fraud detection.

Things went so beyond norms that even state-owned media outlets like CCTV and the People’s Daily have criticized online celebrities like Cai for creating illusions of extraordinary popularity and great recognition through data fraud. But these behaviors have not been terminated, for that the state power sometimes utilizes the massive fan base to spread its own patriotic messages.

So far, there has been no clear sign of dying down for this trend of fan-fueled fake fame. As long as there are dedicated fans, new idols will come forward and reach the top on the Super Hashtag. And by then, there won’t be another Jay Chou to stop them.